December 2002 (Part 1)

SELECTION OF QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

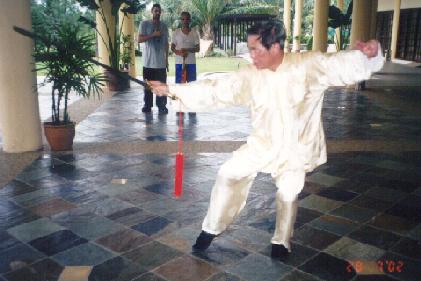

Sifu Wong demonstrating the Wudang Sword

Question 1

Were you trained in the exact same way a Shaolin martial monk was trained many centuries ago? And if so do you teach that same way also?.

— Chris, Australia

Answer

No, my training was different from that of the Shaolin monks many centuries ago, though the principles were similar. While my training was hard compared to that of modern students, mine was easy compared to that of the Shaolin monks.

Shaolin monks spent many months, sometimes a few years, doing odd jobs like chopping firewood and fetching water before they were allowed to learn kungfu. I had to spend only a few nights doing odd jobs like sweeping the floor of the training hall and preparing tea for my seniors, although I volunteered to continue performing those tasks for many years.

Shaolin monks spent many years training their basic stances before practicing combat sequences, but I spent only a few months, though I continued my training of the basic stances.

Shaolin monks began their kungfu career with chi kung exercises like “Eighteen Lohan Hands” and “Sinew Metamorphosis”, and chanted sutras and practiced meditation everyday from the first day of their training. I formally learned chi kung many years after my kungfu training, and learned meditation and sutra chanting much later. Hence, in terms of combat application or internal force, I am nothing compared to an average Shaolin martial monk a few centuries ago.

The way I teach is also different from the way I trained, although, again, the principles are similar. I spent many years doing kungfu first, then I had a chance to learn chi kung. Later, I had a rarer chance to learn meditation. I spent many years learning forms, only then did I learn combat application and internal force development. But my students learned kungfu, chi kung and meditation right from the start of their training.

I often told my students that I was very lucky to have learnt Shaolin Kungfu, but that they were luckier than me, and I was proud of that. Twenty years ago my typical student could attain in three years what I would have taken ten years to learn.

Now it is even more amazing. Students of my Intensive Chi Kung Course and my Intensive Shaolin Kungfu Course can attain in three days or five days respectively skills like entering into a meditative state of mind, generating energy, developing internal force and effective application of kungfu techniques for combat, which I took many years to achieve.

The intensity of the skills, of course, is different. A chi kung student can generate energy flow after three days, and a kungfu student can apply Shaolin techniques for combat after five days of learning from me, but they do not have the same level of skills I had after ten years of training.

Yet, it is really amazing, even to me, that they can achieve such skills — not merely knowing the techniques theoretically — after a few days of intensive training. Twenty years ago, if someone were to tell me that this was possible I would not believe him.

Question 2

Could you please give some insight on how your training was like on a daily basis ?

Answer

My training procedure changed as I progressed from elementary to advanced level. At first I spent a lot of time on form practice. At the intermediate stage I emphasized on force training and combat application. At the advanced level I focused on spiritual cultivation. The following gives a composite idea of my daily training.

I sing praises to Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, reconfirm my vows, chant the Dhayrani of Great Compassion and the Heart Sutra, and share the blessings derived thereof. Then I practice chi kung exercises like “Lifting the Sky”, “Golden Bridge”, “Sinew Metamorphosis” or “Small Universe”. Next I go over a kungfu set, and some combat sequences. I conclude my training with meditation.

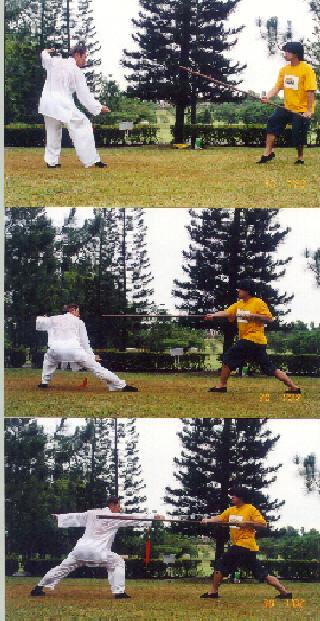

Participants at the Special Taijiquan Course in Malaysia in July 2002 learning the Wudang Sword. From left: Roberto (partly hidden), Angel, Jorge, Anthony, Jeffrey and Inaki.

Question 3

You mention in your website that a real kungfu master would find a Siamese boxer formidable. Does Siamese Boxing practice internal force? What makes a Siamese boxer so hard to overcome?

Answer

I once asked my sifu, Sifu Ho Fatt Nam, what martial art he found most formidable. He said that apart from Chinese kungfu, which was a class apart, the most formidable martial art was Siamese Boxing.

I knew my sifu's opinent was invaluable. He was a former professional Siamese Boxing champion, earning his living in the boxing rings and having fought literally hundreds of matches. Later when he helped his sifu to teach Shaolin Kungfu during a time when challenges amongst masters were not uncommon, he had been challenged by many martial artists and he defeated them all.

So I asked my sifu why he thought Siamese Boxing was so formidable. He said that many people thought Siamese Boxing was simple (when compared to kungfu, for example), but actually it was profound and very effective for fighting. Each technique, each movement was the result of years of actual fighting. If a technique was not useful, it would have been discarded by the professional fighters.

It looked simple, but Siamese Boxing was actually very tricky, my sifu explained. There were many feign moves, which would turn out to be real attacks if the opponents could not respond efficiently. When you blocked a punch, for example, you would find his elbow coming to your jaw. When you avoid his elbow, he would grab your neck and spring up with a knee strike at your ribs.

Siamese boxers were small-sized but they were very tough. Through years of training and actual fighting, they had naturally developed “Iron Shirt” whereby taking a few punches and kicks, which might be devastating to other people, would be nothing much to them.

They were also very powerful and very fast. A typical Siamese boxer, for example, had to kick at a “pinang” tree trunk a few hundred times a day, everyday for many years. Unless one has tremendous internal force, if he blocked a Siamese boxer's kick he would have his arm fractured. Even a kungfu master, especially when the standard of kungfu was so low today, would find it extremely hard to fight with a professional Siamese boxer.

“What about kungfu masters in the past?” I asked. My sifu thought for a while. “A kungfu master in the past would win,” he said. “Take Wong Fei Hoong, for example. His tiger-claw was so powerful. One slash of his tiger-claw would tear or dislocate the boxer's knee.”

Question 4

When would one use Reversed Breathing in Tai Chi? Is it just for spiritual or philosophical reasons, since this is a common Taoist breathing technique, or does this way of breathing also have concrete physical or biomechanical reasons?

— Hans, Germany

Answer

It is useful to give a brief background of Reserved Breathing and Abdominal Breathing, which are two major modes of breathing in Tai Chi Chuan and other styles of kungfu. In Abdominal Breathing the abdomen rises when one breathes in, and the abdomen falls when he breathes out.

The rise and fall of the abdomen is reserved in Reserved Breathing, i.e. the abdomen falls when he breathes in, and the abdomen rises when he breathes out. However this is only the outward form and may be mis-leading although many people identify Abdominal Breathing and Reserved Breathing in this manner.

For example many people, including some Tai Chi instructors, mistake Abdominal Breathing to be diaphragmic breathing, and Reserved Breathing to be chest breathing. This mistake is due to the similarity of the external forms between Abdominal Breathing and diaphragmic breathing, and between Reserved Breathing and chest breathing.

In reality, Abdominal Breathing is different from diaphragmic breathing, and Reserved Breathing is different from chest breathing. They only look the same, but actually are not the same.

In both chest breathing and diaphragmic breathing, what is involved is air, but in Reserved Breathing and Abdominal Breathing what is involved is not air but chi or energy. In chest breathing and diaphragmic breathing, air goes in and out of the lungs when one breathes in and out, with the chest rising and falling or the diaphragm falling and rising respectively.

In Abdominal Breathing, the practitioner takes good energy into his abdomen and disposes off negative energy from his abdomen when he breathes in and out. In Reserved Breathing, when he breathes in he takes good energy into his lungs from the cosmos, and simultaneously disposes off negative energy into his lungs from his abdomen, and when he breathes out he disposes off negative energy from his lungs into the cosmos and simultaneously sends down good energy from his lungs to his abdomen. Of course, those who have no practical experience of energy will not understand what all this is about.

I do not know what do you mean by biomechanical reasons, but one uses different modes of breathing for special physical as well as special spiritual effects. One uses Reserved Breathing when he wishes to exert force in a quick and powerful way but does not want to become tired easily, such as in sparring. He uses Abdominal Breathing when he wishes to employ energy in a gentle way for a long time, such as when performing a Tai Chi Chuan set.

In spiritual cultivation, one uses Reserved Breathing, which is in this case called Cosmos Breathing in our Shaolin Wahnam School, when he wishes to expand his personal energy into the cosmos, as in Zen meditation. He uses Abdominal Breathing when he wishes to circulate his energy flow in a Small Universe, as in Taoist chi kung.

By philosophical reasons, I reckon you mean that Zen or Taoist practitioners use Reserved Breathing or Abdominal Breathing not for any practical benefits but just because these modes of breathing are mentioned in Zen and Taoist philosophies. You are mistaken in both your interpretation of the term “philosophy”, as well as in your assumption of philosophical reasons.

Unlike in the West where philosophy often means intellectualization, in the East, as in the case of Zen and Taoism, philosophy is an explanation of truth. This means that in the West, philosophy comes before practical experience. Western philosophers intellectualize first, then look at the real world for practical examples to justify their intellectualization. In the East, practical experience comes before philosophy. Eastern philosophers look at the real world first, then formalize philosophy to explain what has actually happened.

All special modes of breathing, such as Natural Breathing, Small Universe Breathing, Big Universe Breathing and Dan Tian (Energy Field) Breathing, besides Reserved Breathing and Abdominal Breathing, are used for philosophical reasons, but not in the way you think.

From centuries of practical experience, generations of masters noticed that certain modes of breathing resulted in some special benefits, and they formalized philosophies to explain these breathing modes and their benefits. Modern students, wishing to benefit from the masters' work, practice these different breathing modes for reasons explained in the philosophies.

It is not, as you implied, that some smart guys invented some philosophies from their intellectual reasoning, then invent some breathing methods to justify their philosophies.

Question 5

Are there effects in combat applications that cannot be obtained while using Abdominal Breathing, e.g. the power of a punch, or does Reversed Breathing only influence the inner alchemy?

Answer

One can execute a powerful punch using Abdominal Breathing, but if all other things were equal, a punch executed with Reserved Breathing would be more powerful. On the other hand, again if all other things were equal, a combatant using Abdominal Breathing would have more stamina than another using Reserved Breathing.

Abdominal Breathing or any other special modes of breathing can bring about any combat application effects. I do not know what you mean by inner alchemy. But if you mean to ask how Reserved Breathing or any other mode of breathing affects one's body chemistry, I do not know the answer.

Nevertheless, I do not think any established authorities in kungfu attempted to find out the answer, because what they were interested in was not what chemicals were produced but how effective these different modes of breathing could be used for combat as well as non-combat purposes.

Moreover, a skilful combatant would not bother to reason which breathing mode he should use, how and why; he would spontaneously use the mode that is most effective for the situation.

Combat application of the Wudang sword against the Shaolin staff. Chun Nga attacks Sifu Wong with a horizontal sweep of his Shaolin staff. Sifu Wong lowers his body backward to avoid the sweep, then moves forward, without moving his legs, to strike Chun Nga with his Wudang sword.

Question 6

On page 58 of your great “Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan” you write that “Playing the Lute” is a “kao” technique. I'm afraid to say that I cannot see the “kao” in “Playing the Lute”. Please let me know where the kao is in this posture, and probably also in “Raising Hands”.

Answer

“Kao” means “lean against” or “support”. In this Tai Chi Chuan context, it refers to a part of the body, such as the arm or the hip, to support a combat application implemented by other parts of the body.

In the pattern “Playing the Lute”, the “kao” or “support” is the forearm near the elbow. As your opponent attacks with a right thrust punch, for example, grip his right wrist with your right hand, and using your left forearm near the elbow for support, fracture his attacking right arm, or dislocate his right elbow.

In the pattern “Seven-Star Anchor” of Chen Style Tai Chi Chuan — where I have figuratively translated “kao” as “anchor” — the “kao” or “support” is the elbow. Let us say your opponent again attacks you with a right thrust punch. Grip his right wrist with your right hand, simultaneously place your left hand on your left hip so that your left elbow protrudes out, and pull him to fall forward onto your left elbow.

“Raising Hands” is not normally used as a “kao” technique as a “support” as in “Playing the Lute” and “Seven-Star Anchor”, but it may be used as “kao” for “leaning on”, as in the Ready Position in Pushing Hands.

Another apparently simple but deadly application is to ward off and simultaneously counter-attack. This time your opponent attacks you with his left hand. You respond with “Raising Hands”, warding off his left forearm with your left forearm and simultaneously striking his throat or eye with your left hand while your right hand is held near your left elbow as a guard-hand.

Question 7

There have been lots of Chinese movies portraying Wutang as the champion of the sword style side by side with Shaolin Temple as the champion of the staff such as the Drunken Staff. Could you tell us when the sword style was first developed in Wutang and when it turned to become very famous?

— Thammarath, UK

Answer

Your spelling of "Wutang" is phonetic, whereas my spelling of "Wudang" is according to how it is spelt in Romanized Chinese. Please note that "Wudang" is pronounced as /wutang/, and not as /wudang/, as the Romanized Chinese /d/ is pronounced like /t'/ in English.

There is a saying in kungfu circles as follows: “Shaolin staff, Wudang sword”, indicating that Shaolin Kungfu is famous for the staff whereas Wudang Kungfu is famous for the sword. These two weapons are also characteristic of the two respective styles of kungfu.

Shaolin philosophy is marked by compassion, and the staff manifests this quality of compassion as it has no sharp edges or pointed tips to hurt the opponent seriously. The sword manifests the characteristic of fluidity and gentleness of Wudang Kungfu.

According to legends, the Shaolin staff techniques were first taught by Jinnalou, an Indian Buddhist monk who stayed at the Shaolin Monastery in China as a cook during the Tang Dynasty. Everyday he used a long, heavy stick to stir a huge pot of rice.

One day bandits attacked the monastery. Jinnalou defeated them single-handedly. Hence, after that he taught the staff techniques at the monastery. However, today there are no Shaolin staff sets named after him.

The Wudang sword was developed during the Song Dynasty by Zhang San Feng himself, the first patriarch of Wudang Kungfu. Zhang San Feng first practiced Shaolin Kungfu at the Shaolin Monastery. Later he retired to the Wudang Mountain to cultivate Taoism, and where he also developed Wudang Kungfu, which later became Taijiquan.

Zhang San Feng was an expert of the sword, which he probably learned at the Shaolin Monastery. He transmitted Wudang Kungfu, including the Wudang sword, to generations of Taoist priests who were famous for their swordsmanship. In fact these Wudang priests were better known for their sword techniques than their unarmed techniques.

However, centuries later when Wudang Kungfu evolved into Taijiquan, the sword was less emphasized and unarmed combat became more prominent. The sword is the most important weapon in Taijiquan, but today the Taiji sword is better known for demonstration than for combat. While the Taiji sword evolved from the Wudang sword, they are quite different.

Question 8

I recently read a newsletter about how today boxing is close to or even superior to kungfu and karate. I know you have said that karate, which is now a sport, and kungfu, as far as wushu and pretty kung fu forms go, will be defeated by boxing. Please forgive me if I misquote you..

— Mark, USA

Answer

Yes, those who practice so-called kungfu without combat application, like wushu or external kungfu forms, will be readily defeated by boxers. This type of kungfu is the norm today. Traditional kungfu with combat application and internal force training is rare.

But I did not mention that karate exponents would be defeated by boxers. Karate exponents can be formidable fighters; they practice sparring as an integral part of their training. Like boxers, whose training is mainly sparring, karate exponents can defeat kungfu gymnasts and wushu gymnasts easily, as training for combat is never a part of these gymnasts' training.

But this does not necessarily make kungfu gymnastics or wushu gymnastics inferior to boxing or karate. It depends on one's criteria for consideration. If one thinks of combat efficiency, boxing and karate are better; but if he thinks of health and elegance, kungfu gymnastics and wushu gymnastics are superior.

But if he has the opportunity to practice genuine, traditional kungfu, which is rare today, it is the best. The reasoning is straight-forward. Boxing and karate provide combat efficiency, but may be detrimental to health. Kungfu gymnastics and wushu gymnastics provide health and elegance but lack combat efficiency. Genuine, traditional kungfu has everything, and more; it leads to spiritual attainment.

Question 9

I am currently training in a kungfu style called Blue Dragon. My teacher always says that whenever a boxer throws a jab, just step back or do blocking techniques. I have been in several fights to know that if you are not quick, many jabs will land on your face. I was wondering what would be your opinion about the superiority of boxing and what would be some basic tactics you would use against boxers?

Answer

I am sorry I do not know about Blue Dragon Kungfu, so my reply will be based on the Shaolin Kungfu that I practice.

Boxing looks simple but is actually very effective for fighting. If one has to abide by its rules, it is most effective. This is logical as it has been developed by professionals who earn their living fighting in the boxing rings in this way. This is an important point many people overlook. Worse, they even attempt to fight like boxers, such as throwing away their stances and bounce about.

They also overlook that many boxers are professionals — they fight to live. Most other martial art masters are amateurs — they practice their arts as hobbies. There is a huge difference in standard between professionals and amateurs.

Yet, when many Western boxers came to China in the 19th century, they were convincingly defeated by kungfu masters fighting in boxing rings according to boxing rules, such as no gripping, no throwing, no kicking, no elbowing, and no poking at eyes or hitting at genitals.

This showed that there was something in kungfu which had a big edge over boxing. To me, this something in kungfu was internal force, wide range of techniques and use of tactics and strategies.

If a boxer throws a jab at you and you step back to block using a typical kungfu defence pattern, you would be responding unfavourably and playing into his tricks. A boxing jab is technically faster than a block, and his intention is not to hit you but to confuse you or to tempt you to make a response so that he would follow up rapidly with a series of real attacks.

Then what should you do? Don't step back or block but lean your body backward and give him a side kick as he jabs. You would hit him at about the same time he redraws his jab. This is the tactic of “long against short”.

His jab is comparatively short, and your kick is long. Moreover by shifting your body backward, even you have not moved your feet, you have avoided the reach of his jab, without the need to block. Immediately move forward, brush aside his hands and thrust a punch into his chest.

Alternatively, as he jabs, squat down, move your body slightly forward, and simultaneously strike his abdomen with your fist. This is using the tactic of “avoiding his strong point, attacking his weakness”. Immediately rise up and give him a thrust kick at his chest, followed by stepping forward and hanging a revered fist at his temple.

The boxer may complain that what you have done is against the rules, forgetting that in a real fight combatants need not follow any rules. But if you wish to follow certain rules like no kicking, no gripping, no throwing, etc, the following techniques would be useful.

As the boxer jabs you with his left hand, move your left leg diagonally forward, turn right about into a right Bow-Arrow Stance, and simultaneously swing your left arm down into his left forearm. This is the tactic of “hard against soft”. His jab will not reach you because you have moved diagonally forward. If your arm is powerful, your downward swinging attack may fracture his jabbing arm.

Immediately turn left about into the left Bow-Arrow Stance and simultaneously swing your right fist upward into his body or face. Then move your right leg diagonally forward into the right Bow-Arrow Stance and simultaneously swing your left fist upward into his body or face. Immediately move your right leg a small step forward into a side-way Horse-Riding Stance and strike your right fist into his abdomen.

The amazing point is that almost irrespective of how the boxer responds, you can use these techniques effectively against him! For further information, please refer to my articles on The Flowing Characteristic of Taijiquan and The Wave Tactic of Choy-Li-Fatt Kungfu.

If you practice the above sequence of techniques fifty times a day for six months, you will find that when you apply it on a boxer he often becomes quite helpless. This can give you an idea of the superiority of kungfu.