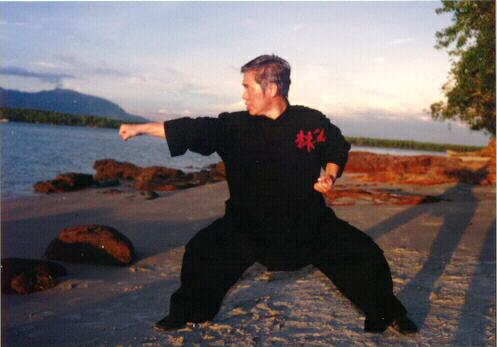

COMBAT EFFICIENCY, HEALTHY, VITALITY, HISTORY, PHILOSOPHY, AND SPIRITUAL CULTIVATION

Shaolin Kungfu

Question

I would like to study more types of Chinese martial arts, because as someone who has spent a while reading and studying self-defense, the Chinese arts seem to be some of the best.

-- John, USA

Answer

There are many good reasons to say Chinese martial arts are the best. First we list out the criteria for comparison, then we compare the various martial arts.

Different people, understandably, may hold different criteria, but it is reasonable to assume that most will agree the following criteria are significant: combat efficiency, health and vitality, history and philosophy, spiritual cultivation.

Because there is a far greater range of techniques and force training in the Chinese martial arts than in any other martial arts, it is logical to conclude that the Chinese martial arts have the greatest range for combat efficiency.

This is not to say that a Chinese martial artist is necessarily more combat efficient than a martial artist of other systems, because one who trains well in two or three techniques and force development methods can be better than another who trains badly in thirty or forty techniques and methods.

This actually is the de facto situation today. Generally a black-belt with three years' experience in any Japanese or Korean martial art is more combat efficient than a Chinese martial artist who only practises external forms for thirty years.

Chinese martial arts pay as much attention to health and vitality as to combat efficiency, whereas other martial systems neglect health for combat efficiency. The underlying principle in Chinese martial art philosophy is that if you want to be a good warrior, you must first of all have good health and vitality.

A person who has internal injury or is tensed and irritable, for example, cannot be a good fighter. In my opinion, the routine training itself of karate, taekwondo, kickboxing and Western Boxing, for example, brings about much internal injury and tends to make the practitioners tensed and irritable.

I recall a very meaningful comment my master, Sifu Ho Fatt Nam, once told me many years ago. “In Shaolin training even a weak, sickly person will eventually become strong and healthy; in the other foreign arts a practitioner hurts himself even before he starts to spar with his training partner.”

There are many ways the practitioner hurts himself in his solo training. Damaging his hands and legs in hard conditioning, tensing his muscles in form practice, and screaming and grimacing to look fearsome are some examples.

Chinese martial arts pay much attention to chi, whereas other martial systems do not. Although the Japanese and Korean arts also talk about ki (their word for chi), from the chi kung perspective their chi training is superficial.

A karate or taekwondo practitioner, for example, soon pants for breath after training for about 15 minutes, and pour in water to quench his thirst. A Chinese martial artist may train strenuously for an hour and yet needs not drink any water.

A karate or taekwondo practitioner is tired out after training, and is left with less energy than when he started his session. A Chinese martial artist is fresh and has more energy than before he started.

The management of chi, or energy, in the Chinese martial arts not only enables the practitioners to develop internal force, but also contribute significantly to their health and vitality.

Chinese martial arts not only have the longest history, they also have been developed by the biggest population of the world. This tremendous time and volume have enabled the Chinese martial arts to develop a richness of philosophy which no other philosophies of other martial systems can ever compare.

For example, while other martial artists are mainly concerned with their immediate attack and defence, Chinese martial artists employ tactics and strategies. In other words, a Chinese martial artist does not merely strike an opponent with a punch or defend against his kick, but he will manoeuvre his opponent in such ways that he can use his strong point against his opponent's weakness.

Besides attaining combat efficiency, health and vitality, Chinese martial artists also cultivate spiritually. Some other martial arts like aikido and judo, and even karate and taekwondo, also mention spiritual cultivation, but there is a qualitative as well as quantitative difference between them and the greatest of the Chinese martial arts like Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan.

Indeed Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan were initially developed for spiritual cultivation; combat efficiency, health and vitality were later bonuses! Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan do not just talk about spirituality; their practice itself is a programme of spiritual cultivation. Hence, in Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan, as well as many other Chinese martial arts, meditation which is the training of mind or spirit, forms an integral part of the arts.

When you consider these criteria, you will find it justifiable to regard Chinese martial arts as the best. But you must be careful that if you want these benefits as described above, you must practise a genuine Chinese martial art that gives these results.

To practise a genuine Chinese martial art was a very rare opportunity in the past. That was one main reason why Chinese martial art students had great reverence for their teachers.

Today it is still a very rare opportunity, but it is easy to practise diluted Chinese martial arts which provide only external demonstrative forms.

There is another important point to take note. There is a crucial difference between studying and practising martial arts.

With the availablity of information today, studying a martial art — i.e. reading about it to understand it better — is easy. Practising it, even if you have the rare opportunity to learn it from a real master, demands much time and effort which most people are not ready to give.

The above is taken from Question 2 of Dec 1999 Part 2 of the Selection of Questions and Answers.

LINKS

Courses and Classes